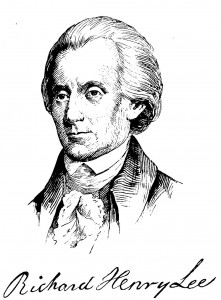

When Americans celebrate publication of the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July, there is seldom reflection upon the many dramas preceding that fateful day. This is the third of a three part series focused on Richard Henry Lee, who placed the question of independence before the Continental Congress in June, 1776. Take a moment to gain the insight in the momentous moment to propose independence by reading Part One and Part Two.

When Americans celebrate publication of the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July, there is seldom reflection upon the many dramas preceding that fateful day. This is the third of a three part series focused on Richard Henry Lee, who placed the question of independence before the Continental Congress in June, 1776. Take a moment to gain the insight in the momentous moment to propose independence by reading Part One and Part Two.

The day had been one of deep contemplation for Richard Henry Lee. He had begun the day by cursing the rifle that misfired and took four fingers from his hand. He had spent time in fond reverie with thoughts of his departed wife Anne. Turning to the business of the day he had considered the resolution for independence and how fate had chosen him to offer it. The possible consequence of that resolution had brought visions of being gutted, burned and beheaded for treason and an uncomfortable intrusion on his consciousness. The time to put himself at risk of the horrifying punishment was near.

Time to Propose The Resolution for Independence

The congressional discussions regarding the powder problems at Eve’s mill came to a close. Richard Henry Lee sought recognition from President Hancock. As he did so, Lee one last time reflected upon being hung, mutilated, burned, and beheaded then put those thoughts aside in the knowledge that no other delegate was in a position to move the Continental Congress toward independence. He rose and placed before Congress the following resolution:

“Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.”

Quick Support from John Adams, Hesitation from the Rest of Congress

Quick Support from John Adams, Hesitation from the Rest of Congress

John Adams would quickly second the resolution and join Lee in the treasonous act.

Other delegates did not offer immediate support. Their actual response was a motion to delay consideration of Lee’s proposal to declare independence. Though Lee understood that many delegations had not received instructions on independence, he thought the time to declare was now. The discussions of naval vessels, South Carolina troops and concerns over gun powder had clearly demonstrated the need. An army and a navy needed something to fight for.

Though frustrated by the proposed delay, he knew if there were to be a delay, those delegates seeking independence instructions from their states needed a strong reminder regarding the arguments in favor of independence. Debates on the resolution and proposed postponement took place on June 8th and 10th. During that time, Lee took the opportunity to make the case for independence.

Richard Henry Lee’s Argument for Independence

Richard Henry Lee’s Argument for Independence

Lee forcefully warned that independence was inevitable, that the historic moment was upon them, the people were ready and that postponement would be folly:

“The time will certainly come when the fated separation between the mother country and these colonies must take place whether you will or no, for it is so decreed by the very nature of things by the progressive increase of our population, the fertility of our soil, the extent of our territory, the industry of our countrymen, and the immensity of the ocean which separates the two countries.

And if this be true, as it is most true, who does not see that the sooner it takes place, the better? — that it would be the height of folly not to seize the present occasion when British injustice has filled all hearts with indignation, inspired all minds with courage, united all opinions in one, and put arms in every hand? And how long must we traverse three thousand miles of a stormy sea to solicit of arrogant and insolent men either counsel or commands to regulate our domestic affairs? From what we have already achieved it is easy to presume what we shall hereafter accomplish.

Experience is the source of sage counsels and liberty is the mother of great men. Have you not seen the enemy driven from Lexington by citizens armed and assembled in one day? Already their most celebrated generals have yielded in Boston to the skill of ours. Already their seamen repulsed from our coasts wander over the ocean, the sport of tempests and the prey of famine. Let us hail the favorable omen and fight not for the sake of knowing on what terms we are to be the slaves of England but to secure to ourselves a free existence to found a just and independent government.

Why do we longer delay? Why still deliberate? Let this most happy day give birth to the American Republic. Let her arise not to devastate and conquer but to re-establish the reign of peace and the laws. The eyes of Europe are fixed upon us; she demands of us a living example of freedom that may contrast by the felicity of her citizens with the ever-increasing tyranny which desolates her polluted shores.

She invites us to prepare an asylum where the unhappy may find solace and the persecuted repose. She entreats us to cultivate a propitious soil where that generous plant which first sprang up and grew in England but is now withered by the poisonous blasts of Scottish tyranny may revive and flourish, sheltering under its salubrious and interminable shade all the unfortunate of the human race.

This is the end presaged by so many omens; by our first victories; by the present ardor and union; by the flight of Howe and the pestilence which broke out among Dunmore’s people; by the very winds which baffled the enemy’s fleets and transports, and that terrible tempest which engulfed seven hundred vessels upon the coast of Newfoundland. If we are not this day wanting in our duty to our country, the names of the American legislators will be placed, by posterity, at the side of those of Theseus, of Lycurgus, of Romulus of Numa, of the three Williams of Nassau, and of all those whose memory has been and will be forever dear to virtuous men and good citizens.”

Postponing the Vote on Independence

There would not be a quick vote. It would be postponed for three weeks for two purposes. First, to provide time for delegates to consult with their home states on independence instructions and second for a committee to draft a declaration to be issued in the event the independence resolution were adopted.

There would not be a quick vote. It would be postponed for three weeks for two purposes. First, to provide time for delegates to consult with their home states on independence instructions and second for a committee to draft a declaration to be issued in the event the independence resolution were adopted.

Richard Henry Lee was not on the drafting committee. Lee had to return to Virginia due to the illness of his second wife, who like his first, was named Anne. As Virginia proposed the resolution for independence, it was appropriate that a Virginian be on the committee to draft the declaration that might be issued in support of the resolution. On June 11th Benjamin Franklin nominated Thomas Jefferson to be that Virginian.

Consideration of Lee’s motion was delayed until July 1, 1776.

Though there were debates, discussions and proposals, others in Congress would not officially join Adams and Lee on the slippery steps to torture and beheading for at least three weeks.

An Unprecedented Proposal

The action proposed by Lee was unprecedented in world history. In 1776, the world was made up of empires. The name of the government head varied around the world. An empire might have a king, a czar, an emperor, a pharaoh or a sultan. These rulers would have power sharing arrangements with an aristocracy or nobility. Territory and peoples would be traded among these empires by agreement or war. The change of a ruler meant trading one sovereign for another.

Through human history there had been changes in the relationships between the ruler and the ruled. Some, like the Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights have become quite celebrated attaining nearly sacred status. Many have been touted as precursors or inspirations for the American colonies. Such analogies are misplaced and mistaken.

The actions that the Americans would take following Richard Henry Lee’s resolution would be like nothing that had happened before. The resolution for American independence proposed creating a nation without a ruler. That was not an evolution from English tradition, it was a rejection of English tradition.

Something exceptional in world history was happening in America in 1776.

Get the full story with the book Creating the Declaration of Independence available both in print and as an Kindle ebook.

Get the full story with the book Creating the Declaration of Independence available both in print and as an Kindle ebook.

[…] The story continues with The Resolution for American Independence: Part Two and Part Three. […]