Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution guaranteed the right to vote for women across the United States. Constitutional studies usually focus on the Supreme Court and its opinions. This approach often loses the personal stories of the real people behind the Constitution’s every word. The tale of Febb Ensminger Burn and her son, Harry T. Burn is just such a story.

Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution guaranteed the right to vote for women across the United States. Constitutional studies usually focus on the Supreme Court and its opinions. This approach often loses the personal stories of the real people behind the Constitution’s every word. The tale of Febb Ensminger Burn and her son, Harry T. Burn is just such a story.

In 1878 and for the next forty years resolutions to amend the Constitution guaranteeing women’s voting rights were introduced in the United States Congress. The Constitution’s Article V requires a two-thirds vote by both houses of Congress for a proposed amendment to be submitted to the states for ratification.

Forty Years of Congressional Rejection

From 1878 to 1918, the proposed amendments to provide universal suffrage for women failed to achieve the needed two-thirds vote. On June 14, 1918, the required congressional vote was achieved and the following was submitted to the states:

“Section 1. The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Summer of 1920: War of the Roses in Nashville

By August 1920, when the issue came before the Tennessee State Legislature, thirty-five states had approved the resolution. The Constitution requires approval by three-quarters of the states. In 1920, this number was thirty-six. Though only a single state short of ratification women’s suffrage supporters knew victory was not certain. The opposition believed that if Tennessee did not pass the Nineteenth Amendment the law would die. A “war of the roses” took place in Nashville that August.

Tennessee women joined together in writing letters, making speeches, and lobbying legislators. The yellow rose became the symbol of support for women’s suffrage. Red roses were the opposition’s symbol. Members of the Tennessee legislature “showed their colors” by wearing roses on their lapels indicating which side they were on.

Tennessee House Deadlocked

On Friday, August 18, the Tennessee House debated a joint resolution for ratification that had recently passed the state Senate. A count of roses worn by House members showed 49 red and 47 yellow. It appeared the Tennessee House would reject ratification. After a lengthy debate, House Speaker Seth Walker, a proclaimed “anti,” boldly proclaimed, “The hour has come. The battle has been fought and won, and I move . . . that the motion to concur in the Senate action goes where it belongs—to the table.”

This legislative maneuver would effectively kill the resolution and ratification of the amendment. However, Rep. Banks Turner came over to the Suffragist’s side and the vote was deadlocked at 48 for and 48 against. A second roll was taken and the vote remained 48 to 48.

The next vote taken was not to table the resolution, but an actual vote for or against joining the Tennessee Senate in approval.

Harry Burn, Febb Burn and the Crucial Vote

As the crucial vote took place the mind of 24 year old freshman legislator Harry Burn was in conflict. He wore a red rose. He faced reelection in the fall. The issue was contentious among his constituents. A deciding vote either way could decide his electoral fate.

As the crucial vote took place the mind of 24 year old freshman legislator Harry Burn was in conflict. He wore a red rose. He faced reelection in the fall. The issue was contentious among his constituents. A deciding vote either way could decide his electoral fate.

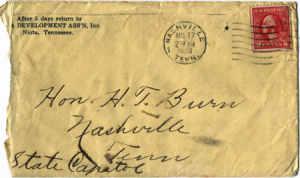

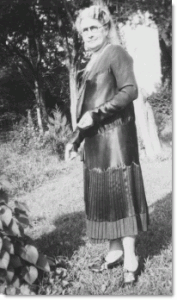

While Burn wore a red rose on his lapel, in his pocket he had a letter from his widowed mother, Febb Burn. Mrs. Burn had written a seven page letter to her son, mostly about family matters. However, in the letter she made clear her wishes regarding her son’s vote on ratification:

“Dear Son, Hurray and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt. I noticed Chandlers’ speech, it was very bitter. I’ve been waiting to see how you stood but have not seen anything yet…. Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt with her “Rats.” Is she the one that put rat in ratification, Ha! No more from mama this time. With lots of love, Mama.”

When the clerk called Harry Burn’s name on the decisive resolution, he voted “Aye”, honoring the wishes of his mother. The Tennessee House approved the resolution 49-47, and universal women’s suffrage became part of the United States Constitution.

When the clerk called Harry Burn’s name on the decisive resolution, he voted “Aye”, honoring the wishes of his mother. The Tennessee House approved the resolution 49-47, and universal women’s suffrage became part of the United States Constitution.

The organized movement to secure a woman’s right to vote is often dated to the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY in 1848. In the 72 following years, there are many stories of those involved in the struggle. In the end, the Nineteenth Amendment and women’s voting rights were secured by a mom’s note and her son’s vote.

[…] voting laws required constitutional amendments.[2] This took place with the 15th Amendment,[3] 19th Amendment,[4] 23rd Amendment[5] and […]