The celebration of American Independence Day on the Fourth of July has come to include parades, barbecues and fireworks. The celebrations would do well to include discussions of how the Declaration of Independence came to be. Part Two of the Birthing of the Declaration of Independence takes place over an ale and a meal in a tavern, with The Committee of Five, having dwindled in reality to just Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, since most members of Congress thought that drafting the declaration was necessary, but not really that important. The prelude to this meeting is found in Birthing the Declaration of Independence: Part One.

The celebration of American Independence Day on the Fourth of July has come to include parades, barbecues and fireworks. The celebrations would do well to include discussions of how the Declaration of Independence came to be. Part Two of the Birthing of the Declaration of Independence takes place over an ale and a meal in a tavern, with The Committee of Five, having dwindled in reality to just Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, since most members of Congress thought that drafting the declaration was necessary, but not really that important. The prelude to this meeting is found in Birthing the Declaration of Independence: Part One.

First Considerations

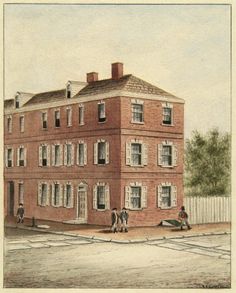

Having placed their order for ale and a serving of the meal being served at City Tavern that evening, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams returned to the reason they had met: moving forward on a document to announce American independence.

Adams, took the lead: “Let’s consider the form this declaration should take. There’s little sense in starting over from scratch. We’re both lawyers, and I think we can find an effective model for explaining why the colonies are breaking from England. It’s also likely to be useful to look at the available, though limited historical parallels. If we lay out a general structure first we can go from there. Whatever general approach we choose, it’s important to remember this declaration must speak to many audiences.”

Adams, took the lead: “Let’s consider the form this declaration should take. There’s little sense in starting over from scratch. We’re both lawyers, and I think we can find an effective model for explaining why the colonies are breaking from England. It’s also likely to be useful to look at the available, though limited historical parallels. If we lay out a general structure first we can go from there. Whatever general approach we choose, it’s important to remember this declaration must speak to many audiences.”

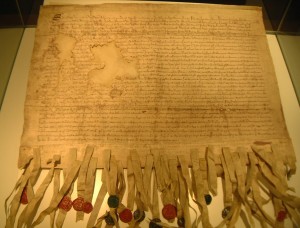

Listening to Adams, Jefferson reflected upon how “declarations” were constructed through history, particularly those lodging complaints against a king. The Scots had done it in 1320, the Dutch had in 1581, and the English in 1689.

The Form of the Declaration of Independence Takes Shape

Though their food and drink had been served, Jefferson and Adams continued to talk as the ale got warm and the food got cold. They concentrated on their task: building a declaration for independence. Given their legal training, it was natural for them to agree upon a format for the declaration similar to a civil complaint used to start a lawsuit:

- A preamble or “whereas” statement explaining the purpose of the document

- A statement of law/philosophy that states the basis for the proposed action

- A list of grievances against the king

- Prior actions taken in response to the king’s acts.

- Apply the law/philosophy to the actions to arrive at the conclusion that independence is the appropriate remedy to the grievances.

It was an outline the two lawyers understood, and thought, so would the intended audiences: the leadership of the other colonies; the governments of France, Spain and England; the Continental Army in New York and elsewhere preparing to defend against expected British attacks; and the American people.

Upon completing the outline and identifying the audience Jefferson remarked to Adams: “The form is familiar, the audience is challenging.”

Adams replied: “It’s just a much larger jury, and we put a great deal of trust in juries.”

Jefferson added: “The largest jury is the American people. Ultimately it will need to be an expression of the American mind and make clear that our independence is simply common sense.” Adams nodded his agreement.

Their selection of form complete, Adams indicated he would convey, out of courtesy, their discussion to the other committee members. Adams asked Jefferson to begin thinking about the content to fill in the form. With this stage of the process finished, they ate their meal, mostly in silence.

As Jefferson drained his stein he became aware of others waiting to speak with Adams. This was unsurprising, considering Adams’ many committee memberships. Jefferson thought to himself: “He’s not much liked, but he’s surely respected.”

Jefferson stood to take his leave. The five foot seven inch Adams showed no notice of the height of the six foot two inch Jefferson and stood as well. They shook hands and Jefferson left City Tavern to return to the apartment he rented from bricklayer Jacob Graff.

Something Really Important: The Virginia Constitution

Walking to Graff House, he thought briefly of his mother’s death a little more than two months ago, and the debilitating headaches he endured for the six weeks following her apparent stroke at 56. No matter, Virginia was writing a constitution and the colonies were on the verge of independence and he was in the middle of it. Though the declaration project with Adams was important the first order of business was Virginia.

Walking to Graff House, he thought briefly of his mother’s death a little more than two months ago, and the debilitating headaches he endured for the six weeks following her apparent stroke at 56. No matter, Virginia was writing a constitution and the colonies were on the verge of independence and he was in the middle of it. Though the declaration project with Adams was important the first order of business was Virginia.

Jefferson really wished he were in Virginia instead of Philadelphia and involved in this declaration business. He would put off considering the declaration for now, and try to find a way to contribute to something truly important, the constitution of Virginia.

The story continues at Birthing the Declaration of Independence: Part Three, Virginia Comes First

[…] Birthing of the Declaration of Independence continues with Part Two: The Format. […]