While the Founding Mother of professional nursing, Florence Nightingale, whose birthday is the midpoint of National Nurses Week, was laboring in the Crimean War and establishing her nursing school in London, trouble was brewing the United States. As in Britain, it would be war to move forward nursing as a profession. The recognition of nursing as a distinct profession and its contribution to public health has its roots in war and the desire of caring, compassionate women to ease the suffering that results from that most awful element of the human condition.

While the Founding Mother of professional nursing, Florence Nightingale, whose birthday is the midpoint of National Nurses Week, was laboring in the Crimean War and establishing her nursing school in London, trouble was brewing the United States. As in Britain, it would be war to move forward nursing as a profession. The recognition of nursing as a distinct profession and its contribution to public health has its roots in war and the desire of caring, compassionate women to ease the suffering that results from that most awful element of the human condition.

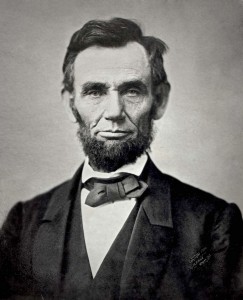

The American Civil War would have a profound effect on the development of the nursing as a profession and in many ways laid the foundation for modern nursing in the United States. Around the time of the Civil War there were only about 150 hospitals in the United States; there were no formal schools of nursing; no nursing credentials, and no “trained” nurses. In England, the first class entered Florence Nightingale’s professional nurse training school on July 9, 1860, four months before the election of Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln would say in his Gettysburg Address, “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here but cannot forget what they did here.” Events that in their day had a major impact on history become gray and forgotten with time. So it is with nursing history.

Lincoln would say in his Gettysburg Address, “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here but cannot forget what they did here.” Events that in their day had a major impact on history become gray and forgotten with time. So it is with nursing history.

The Civil War’s hundreds of thousands of casualties created a need for caregivers and tens of thousands of women offered their services, mostly as volunteers. Reacting to that need, America’s Founding Mothers of Professional Nursing would come to the forefront. Among them would be Dorothea Dix.

In 1861, there was strong opposition to the presence of female volunteers in the camps and hospitals of the Union army. Initial wartime volunteers were viewed no differently from “camp followers,” sometimes mistresses and sometimes wives who followed their soldier men. Early in the War, “respectable” women could not be seen in a military hospital.

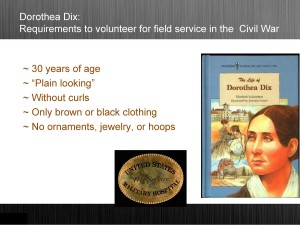

Dorothea Dix organized a march on Washington demanding that women be allowed to treat Union soldiers. She would soon be put in charge of nurses assigned to the U.S. Army and appointed to organize and outfit the Union Army hospitals and oversee the vast nursing staff that the war would require. As superintendent of women nurses, she was the first woman to serve in such a high capacity in a federally appointed role.

Upon her appointment, Dix set standards for nurses that we might find a curious: over 30 years of age; “plain looking”; without curls, only brown or black clothing no ornaments, jewelry, or hoops. While these “requirements” sound strange in the 21st Century, Dix’s rules were in place to make it clear that the nurse’s role was to meet the soldiers’ medical needs. The women she directed were not to be seen as “camp followers”.

Upon her appointment, Dix set standards for nurses that we might find a curious: over 30 years of age; “plain looking”; without curls, only brown or black clothing no ornaments, jewelry, or hoops. While these “requirements” sound strange in the 21st Century, Dix’s rules were in place to make it clear that the nurse’s role was to meet the soldiers’ medical needs. The women she directed were not to be seen as “camp followers”.

Such “standards” notwithstanding, it is estimated that 3,000 nurses served in the war although as many as 30,000 women worked as volunteers. With supplies pouring in from voluntary societies across the north, Dix’s administrative skills were sorely needed to manage the flow of bandages and clothing as the war wore on.

[…] does not include battlefields or the hospitals near them, like the stories of Florence Nightingale, Dorothea Dix or Mary Ann Bickerdyke. Her work to professionalize nursing was in the political arena. Their […]