Clarence Earl Gideon had an eighth grade education and a long criminal history. He had been sentenced to prison for the fifth time. Upon his arrival he began to study law for long hours in the prison library. As the story goes, eventually, with a pencil and paper he scratched out an appeal to the United States Supreme Court that changed the American legal system when the Court decided his appeal in the case of Gideon v. Wainwright. Is that really what happened?

Clarence Earl Gideon had an eighth grade education and a long criminal history. He had been sentenced to prison for the fifth time. Upon his arrival he began to study law for long hours in the prison library. As the story goes, eventually, with a pencil and paper he scratched out an appeal to the United States Supreme Court that changed the American legal system when the Court decided his appeal in the case of Gideon v. Wainwright. Is that really what happened?

The impact of Gideon v. Wainwright on daily life cannot be overstated. Police officers in real life and on television advise those suspected of crime of their right to an attorney every day. The principles announced in Gideon became half of the well known Miranda Warnings. Judges in courtrooms everywhere make inquiries of thousands of defendants about their financial status to determine if they can afford counsel. The Google search “Gideon v. Wainwright” returns 937,000+ results, demonstrating the broad interest in the case.

Part I relates Gideon’s story and the background of the right to an appointed attorney for indigent criminal defendants. The story’s mystique revolves around Clarence Gideon and his producing the appeal. Gideon’s legendary prison library study and pencil written appeals leaves a good feeling about the success of a common man with a cause. Part II explores the legend’s reality.

Gideon’s Belief in the Indigent Right To Counsel and His Prison Experience

On August 4, 1961 Gideon stood in court and advised the judge that the United States Supreme Court said he had the right to a court appointed attorney. In Clarence Gideon: Unlikely World Shaker Jack King dates Gideon’s belief in that right to Missouri in 1928. That year, a Missouri court appointed an attorney for him when he was being prosecuted for burglary. Gideon was only 18.

From 1928 to 1951 he spent over 10 years in prison. Other inmates, who had not had attorneys appointed in their cases, were regularly writing appeals for their convictions. All that time, the “special circumstances”1 rule was in effect. Prisoners, writing their own petitions asserted “special circumstances”, claiming youth, inexperience, or another situation that entitled them to an attorney. A successful appeal required such a claim. This was Gideon’s exposure to the law of appointed counsel while in prison.

In 1928 Gideon was young, a “special circumstance” and received an appointed attorney. He had seen many writing their own appeals insisting they had been entitled to appointed counsel. These experiences likely lead to his 1961 statement in court.

Gideon’s Legendary Petitions Did Not Assert “Special Circumstances”

Gideon’s 1961 petitions to the Florida Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court did not claim “special circumstances”. The first was filed only 45 days after Gideon was sentenced, and contained a novel legal approach, not to be found in the prison library. Why would he do this? How did he do it so quickly?

The Back Story on the Law Always Involves Real People

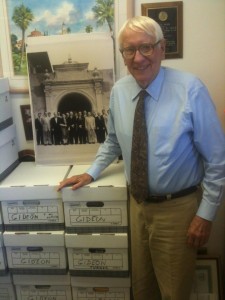

A young Florida Assistant Attorney General, Bruce R. Jacob, argued the state’s case before the United States Supreme Court in the Gideon case. Since then Mr. Jacob has had a distinguished career in the law. He remains active 50 years later as Dean Emeritus and Professor of Law at Stetson College of Law. The Gideon case has remained part of his life. For the 40th Anniversary of the Court’s decision Dean Jacob wrote: MEMORIES OF AND REFLECTIONS ABOUT GIDEON v. WAINWRIGHT. In September, 2013, for the 50th Anniversary Dean Jacob spoke about the case at the University of Florida Law School.

His Stetson Law Review article educates about both the law and the people2 involved in Gideon. His article serves as a reminder that great legal matters are more than court opinions. Real people are involved. Among those in the Gideon story was one Joseph A. Peel, Jr.

Dean Jacob Introduces Joseph A. Peel, Jr.

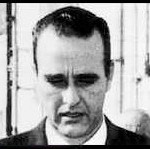

Joseph A. Peel, Jr. was an inmate at the Florida State Prison in Raiford during the time Gideon was writing his appeals. Peel was a convicted murderer. He had been part of a plot to kill Circuit Judge Curtis E. Chillingworth and Chillingworth’s wife Marjorie, of Palm Beach, Florida. Peel had himself been a judge.

Jacob tells the story:

“The Chillingworths disappeared from their oceanfront home one night in 1955, and for five years, their disappearance remained a mystery. Finally, Floyd (Lucky) Holzapfel confessed to their murders and testified—as a star witness—against Peel, who had become a municipal judge in West Palm Beach, that he and Peel had split about $3,000 a week from gamblers and moonshiners for tip-offs when search warrants were issued for raids on moonshine stills or gambling dens. Peel told Holzapfel that Chillingworth, who had become aware of Peel’s operations and was about to “blow the whistle,” had to die. Unfortunately, because Mrs. Chillingworth was with the Judge when he was murdered, according to Holzapfel, she also had to be killed.

Holzapfel and George (Bobby) Lincoln, a moonshiner, drove a small boat to the beach in front of the Chillingworth home. They seized the couple in the beach cottage, bound and gagged them with adhesive tape, and dragged them to the motorboat. The bloodstains were Mrs. Chillingworth’s—she struggled and was struck with a pistol butt. Holzapfel and Lincoln drove the boat four miles offshore, where they wrapped the victims with old army gun belts, weighted the couple with lead weights, and threw Mrs. Chillingworth and the Judge overboard.

Peel was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.”

The Former Judge Peel Looks over Gideon’s Shoulder and More

According to W. Fred Turner, Gideon’s attorney at his second trial, Peel was Gideon’s cellmate and “stood over his shoulder as Gideon wrote and told him what to say.” There’s evidence that Peel did more than that.

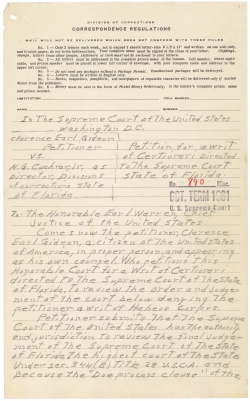

Jacob points out that Gideon’s handwritten court documents are treated as treasures of American history. The Petition for Habeas Corpus to the Florida Supreme Court and The Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court are both available online for anyone to examine.

The caption of the Florida petition is printed in childlike block letters; the body of the petition is in cursive script. The Florida petition’s third page says (in cursive writing): “I Clarence Earl Gideon beg of this court to issue a Writ of Habeas Corpus…” and is signed “Clarence Earl Gideon” at the bottom.3 The two renderings of “Clarence Earl Gideon” on the Florida petition were clearly not written by the same person.

The petition to the US Supreme Court is printed4 in block letters by someone with skill. The printing was not done by the same person who printed the caption on the Florida petition. The only cursive writing on the US petition is Gideon’s blue ink signature.

None of the writing or printing in the body of either petition appears remotely related to Gideon’s notarized signature at the end of each.

Both petitions are written in language like: “Attached hereto and made a part of this petition is a true copy of the petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus…”

These writing skills were not learned in the prison library between August 25, 1961 and January 6, 1962. The absence of a claim of “special circumstances” was not likely Gideon’s idea. Gideon did not scrawl out his petitions, nor came up with their legal strategy.

The story of the determined Gideon studying away in the prison library and then struggling with his pencil to create documents that altered legal history is not accurate.

The former Judge Peel5 was a convicted murderer, but he was a trained attorney.6

Perpetuation of Gideon as a Determined Man in the Prison Library

As noted above, a Google search for “Gideon v. Wainwright” returned 937,000+ hits. A search of “Gideon v. Wainwright” & “Joseph A. Peel, Jr.” returns 2 hits.7 The Gideon story loses some romance if the appellate work was actually done by former judge who arranged the murder of a colleague. In nearly a million examinations of the story, Peel is left out. This protects the romance.

Legal Importance Unchanged, But History Might be Different

Peel’s role has no effect on the legal importance of Gideon v. Wainwright, but does pose some interesting questions. Were the Supreme Court justices enamored with the story of an indigent prisoner handwriting his appeal in pencil? Would the case have been attractive to them if it did not clearly have the stuff of historical legend? Would they have taken it if it were possibly tainted by the involvement of a murdering judge? Would the law today on Right to Counsel be different?

The avoidance of so many in including Peel in the story says something about how sometimes there are things that people just want to believe.

Gideon Ultimately Was Right and So Was the Supreme Court

Gideon’s statement in court: “The United States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by Counsel.” proved to be prescient. Convicted former Judge Joseph Peel, Jr. proved how important it is to have someone trained in the law on your team.

_____________________________________________________________________

1The “special circumstances” requirement is discussed in Part I. Part I’s footnote 4 provides detail.

2 Mr. Jacob’s more recent article Remembering Gideon’s Lawyers is a great personal recollection of the lawyers involved.

3 The body is written in the famous pencil and the signature is in blue ink.

4 The body of the US petition is also written in pencil with Gideon’s signature in blue ink.

5 Peel was not as successful in appellate courts on his own behalf. He lost appeals related to his murder conviction. He was also convicted in federal court for violating the anti-fraud provisions of the Securities Act of 1933, the Mail Fraud Statute, and conspiracy provisions of the federal criminal Code, and lost his appeal in that case.

6 A Stetson University College of Law graduate, Peel died in 1982 of cancer 9 days after being paroled.

7 The only two Google hits from that search are Dean Jacob’s Stetson Law Review Article and Jack King’s Clarence Gideon: Unlikely World Shaker

[…] and paper in the prison library. That picture moved Attorney General Kennedy’s eloquence. Part II takes a look at the accuracy of that […]