All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

This is the first sentence of the Constitution. It appears quite simple. The power to enact laws about the subjects listed in the Constitution is granted to the Congress, and the Congress is the Senate and House of Representatives. Can there be any other reading?

There is sometimes a need for 18th Century words to be translated into 21st Century English. Article I, Section 1 needs no such translation. “All” still means “all”. “Legislative Powers” still means authority to make law. “Granted” still means “given to”.

When the Constitution is viewed as a Power of Attorney, with the People as the principal and the government as the agent, it means that we gave the Congress the power to make law. Art. I, Sec. 1 is the essence of the Constitution.

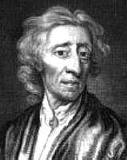

When a person creates a power of attorney for any purpose (health care, financial matters, real estate transactions), authority is given for specific acts to a specific agent, and no one else.[1] The Constitution’s Ratifiers and Framers were well aware of this. They were also influenced in their thinking and constitution creation by John Locke. For Locke, an institution granted the power to make law did not have the authority to give that power away.

Locke: Legislative Power is to Make Laws, not Legislators

Locke: Legislative Power is to Make Laws, not Legislators

In 1690, in his Second Treatise of Civil Government, John Locke wrote:

“The Legislative cannot transfer the Power of Making Laws to any other hands. For it being but a delegated Power from the People, they, who have it, cannot pass it over to others… The power of the Legislative being derived from the People by a positive voluntary Grant and Institution, can be no other, than what the positive Grant conveyed, which being only to make Laws, and not to make Legislators, the Legislative can have no power to transfer their Authority of making laws, and place it in other hands.”

Locke’s 17th Century English is a bit more cumbersome, but in the end, the point is clear. The legislative power is to make Laws, and not to make Legislators. The creation of the modern administrative state has ignored this principal, resulting in the delegation of lawmaking power to the alphabet soup of federal agencies.[2]

There have been various explanations[3] for why the Congress has given away the power that was exclusively given to it in the Constitution’s first sentence.[4] The explanations make little sense.

Important Subjects or Mere Details

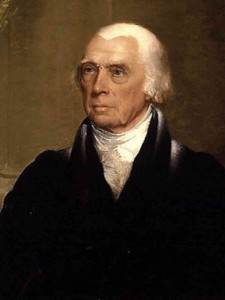

James Madison in Federalist 47 explains why there was a certain mixing of powers among the three branches of government and not a strict separation. Chief Justice John Marshall in discussing the legislative power[5] distinguished between “important subjects” and “mere details.” He wrote that “a general provision may be made, and the power given to those who are to act under such general provision, to fill up the details.” However, neither foresaw such abdication of lawmaking by Congress that would dominate the 20th Century, leaving a legacy for the 21st.

James Madison in Federalist 47 explains why there was a certain mixing of powers among the three branches of government and not a strict separation. Chief Justice John Marshall in discussing the legislative power[5] distinguished between “important subjects” and “mere details.” He wrote that “a general provision may be made, and the power given to those who are to act under such general provision, to fill up the details.” However, neither foresaw such abdication of lawmaking by Congress that would dominate the 20th Century, leaving a legacy for the 21st.

How Congress Fails to Make Laws and Instead Makes Legislators

Here are but two examples Congress not creating laws, but creating legislators: The Communications Act tells the Federal Communications Commission to grant broadcast licenses “if public convenience, interest, or necessity will be served thereby.” The statute grants nearly complete discretion about an issue that is categorically fundamental to the regulation of broadcasting. The Motor Vehicle Safety Act directs that “the Secretary of Transportation shall prescribe motor vehicle safety standards. Each standard shall be practicable, meet the need for motor vehicle safety, and be stated in objective terms.” This statute as well provides the agency nearly complete discretion. The FCC and Transportation Secretary have not been directed to fill in the “details” of enforcement, they have unconstitutionally been given the power to make law.

Here are but two examples Congress not creating laws, but creating legislators: The Communications Act tells the Federal Communications Commission to grant broadcast licenses “if public convenience, interest, or necessity will be served thereby.” The statute grants nearly complete discretion about an issue that is categorically fundamental to the regulation of broadcasting. The Motor Vehicle Safety Act directs that “the Secretary of Transportation shall prescribe motor vehicle safety standards. Each standard shall be practicable, meet the need for motor vehicle safety, and be stated in objective terms.” This statute as well provides the agency nearly complete discretion. The FCC and Transportation Secretary have not been directed to fill in the “details” of enforcement, they have unconstitutionally been given the power to make law.

It’s The Congress

For those who are unhappy with orders issued by the president, whether the president is named Clinton, Bush, Obama or Trump, consider that the real source of the problem is that Congress has given away its power to the executive. The Congress was to make law, something it engages in only rarely. The judiciary has been complicit in allowing Congress to abdicate its legislative duties. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch has been a staunch proponent of reigning in the legislative and judicial delegations to executive agencies. Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s writings indicate agreement with Justice Gorsuch, so there is reason to hope that in the future our elected representatives may be forced to actually pass laws rather than passing the buck.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Certainly a successor agent may be named in the event the chosen agent is unwilling or unable, but there is always a single designated agent at any given moment. If you have given the power to make choices about your health to someone, you have not given that person the power to let someone else make those choices.

[2] States are equally as guilty.

[3] See, Theory of Legislative Delegation, 68 Cornell Law Review 1, 22 (1982)

[4] While the Preamble opens the Constitution and states the purpose, it grants no authority and imparts only understanding. The Constitution is understood by keeping the Preamble in mind, but the first sentence with legal effect is Art. I, Sec. 1.

[5] Wayman v. Southard (1825)

[…] “Section 1. All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” […]