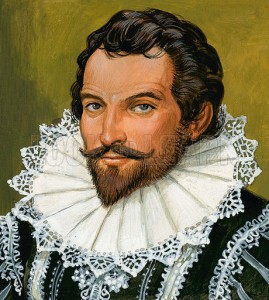

Sir Walter Raleigh of the late 1500’s is known for a number of things. He was a great explorer[1] of the New World, both North and South America. He is either credited or cursed for promoting tobacco in England. He is cited as an example of the consummate gentleman for putting his cloak on a puddle to prevent Queen Elizabeth I from stepping in it.[2] For purposes of the US Constitution, Raleigh’s greatest contribution was his demand that he be able to face the witness against him during his trial for treason in 1603.Sir Walter Raleigh of the late 1500’s is known for a number of things.

Sir Walter Raleigh of the late 1500’s is known for a number of things. He was a great explorer[1] of the New World, both North and South America. He is either credited or cursed for promoting tobacco in England. He is cited as an example of the consummate gentleman for putting his cloak on a puddle to prevent Queen Elizabeth I from stepping in it.[2] For purposes of the US Constitution, Raleigh’s greatest contribution was his demand that he be able to face the witness against him during his trial for treason in 1603.Sir Walter Raleigh of the late 1500’s is known for a number of things.

Raleigh’s demand was denied and a written statement of an alleged co-conspirator was used as evidence against him, without the witness appearing in court to answer questions about the statement. Raleigh was convicted and spent the next thirteen years in prison.[3] The case is studied in law schools today and the US Supreme Court referred to the problems with Raleigh’s trial in Crawford v. Washington 400 years later.

The Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause

The abuses of the English trial system in presenting evidence in criminal trials that a defendant could not challenge and Raleigh’s story in particular were well known to the Founders of America. One protection against such abuses is the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment:

“…in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right…to be confronted with the witnesses against him.”

Right is Rooted in Biblical and Roman Practice

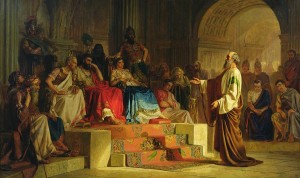

There is little in the records of the First Congress about The Confrontation Clause to point to its foundations, justifications, or purposes.[4] However, the right to confrontation has existed in many societies since Biblical times. The traditions of both Hebrew and Roman law required witnesses to testify in person in the defendant’s presence. The Roman governor Festus responded to calls for the summary execution of the Apostle Paul: “It is not the custom of the Romans to deliver any man to destruction before the accused meets the accusers face to face.”

There is little in the records of the First Congress about The Confrontation Clause to point to its foundations, justifications, or purposes.[4] However, the right to confrontation has existed in many societies since Biblical times. The traditions of both Hebrew and Roman law required witnesses to testify in person in the defendant’s presence. The Roman governor Festus responded to calls for the summary execution of the Apostle Paul: “It is not the custom of the Romans to deliver any man to destruction before the accused meets the accusers face to face.”

Confrontation Right Lost in England and the Colonies

When Christianity became the established religion of the Roman Empire, the right to confrontation in criminal cases was recognized in the early years. Over time, the right faded and witnesses were examined in private without the defendant’s attending. This would become the typical process in England.

As evidenced by Raleigh’s trial and conviction, there was not a recognized right of confrontation in England at the time the American colonies were established. The standard procedure was to examine witnesses in private. As a practical matter, the right of confrontation simply did not exist and trials were conducted with evidence that could not be questioned by the defendant.

It is this English and colonial history that influenced the drafters of state constitutions and the United States Constitution to include confrontation clauses as a critical procedural protection of the inalienable right to liberty.

In England and British North America during the seventeenth century courts did not require the personal appearance of witnesses in court. Prosecutors customarily used witness depositions instead of live courtroom testimony despite defendant demands for face-to-face confrontation.

Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1603 treason trial traditionally is one of the most often mentioned examples of such abuses of the power to prosecute crimes. Raleigh was accused of planning the assassination of King James VI. When the prosecution relied upon a sworn and signed declaration of guilt from Lord Cobham, Raleigh’s purported co-conspirator, Raleigh demanded Cobham’s courtroom presence. Raleigh wanted to confront and cross-examine Cobham. After Raleigh’s demands were rejected he was convicted. In accordance with the law of treason he was sentenced to death, but the king spared his life.

Experience Leads to Protection of Liberty, Restoration of the Right of Confrontation in America

Injustices similar to that suffered by Raleigh took place during America’s revolutionary era. America’s Founders were well aware of Raleigh’s famous case and their own colonial experiences were fresh in their minds. This knowledge and experience led to protections for the right of confrontation in the United States.

Injustices similar to that suffered by Raleigh took place during America’s revolutionary era. America’s Founders were well aware of Raleigh’s famous case and their own colonial experiences were fresh in their minds. This knowledge and experience led to protections for the right of confrontation in the United States.

The Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause can be traced to the early state constitutions. In 1776, Virginia was the first state to adopt a Declaration of Rights. The Virginia document included a defendant’s right “in all capital or criminal prosecutions . . . to be confronted with the accusers and witnesses.” By 1784 seven other states had included confrontation clauses in their constitutions. This trend culminated in the adoption of the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause.

James Madison, father of the Bill of Rights, on June 8, 1789 introduced to the House of Representatives a proposal that would become the Sixth Amendment, drawing substantially from the language of the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

While the history of the right of confrontation can be traced to biblical times, the right had been lost in England and the colonies by the time of the Revolution. The full restoration of the right was another contribution to human freedom and liberty that grew from the Founding of America.[5]

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[2] Though this famous story is likely to be a myth.

[3] Though he was released from prison in 1613 that was not the end of Raleigh’s legal problems. He was ultimately beheaded in 1618.

[4] Many issues addressed in the Bill of Rights (First Ten Amendments) were the subject of debate, and records of these debates are instructive as to what the drafters of the amendments meant. When the record is limited that is an indication that a concept had general agreement.

[5] The US Supreme Court case of Crawford v. Washington provides more history on the Confrontation Clause, and commendably brought the law as stated by the Supreme Court, more closely in line with the plain language of the Sixth Amendment. Since the amendment was adopted the Right of Confrontation has been plagued with “exceptions” that allowed statements made by witnesses not in court to be used as evidence in criminal cases. Crawford did much to limit exceptions based upon a showing that the out of court statements were “reliable”, but the Right of Confrontation has not been as strongly protected as one would expect from the amendment’s clear language.

[…] Walter Raleigh of the late 1500’s is known for a number of things. He was a great explorer[1] of the New World, both North and South America. He is either credited or cursed for promoting […]