“The Tenth Amendment is the foundation of the Constitution.”

– Thomas Jefferson

Among the questions raised by opponents of the Constitution during the ratification debates was the lack of an express limit on federal power, and that it would be a danger to individual freedoms and to the powers of the states.

In response to this concern the Constitution’s proponents[1] argued that the central government could exercise only the powers named in Article I.[2] This was argument developed from agency law, something the drafters at the Constitutional Convention were very familiar with. In various debates, writings and publications, the Federalists assured the states would retain power over most domestic issues, including, but not limited to:

- governance of religion

- training the militia and appointing militia officers

- control over local government

- most crimes and state justice systems

- family affairs

- real property titles and conveyances

- wills and inheritance

- the promotion of useful arts in ways other than granting patents and copyrights

- control of personal property outside of commerce

- the law of torts and contracts, except in suits between citizens of different states

- education

- services for the poor and unfortunate

- licensing of taverns

- roads other than post roads

- ferries and bridges

- regulation of fisheries, farms, and other business enterprises

Neither the arguments, nor the listings were satisfactory to the Anti-Federalists. As argued by Patrick Henry:

Neither the arguments, nor the listings were satisfactory to the Anti-Federalists. As argued by Patrick Henry:

“If we trust our dearest rights to implication, we shall be in a very unhappy situation.”

The Federalists promised to address these concerns with amendments if the Constitution were ratified.

The Tenth Amendment

Not wishing to rely upon the implications of Agency principles alone, many state conventions included recommendations for a Bill of Rights along with their ratification resolutions. The new government went in effect in 1789, and the concerns of the Anti-Federalists remained alive.

Shortly after the First Congress convened, New York and Virginia filed applications for an Article V[3] Convention on Amendments. The Federalists were in control of Congress, and led by James Madison, to keep their promises and to avoid an Article V convention, proposed twelve amendments. The Tenth Amendment reads:

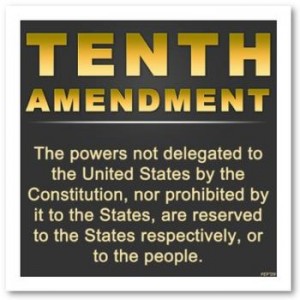

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

The Tenth Amendment had been the twelfth offered, but the first two weren’t ratified.[4] The Tenth Amendment in reality codified the agency principles that had been relied upon by the Federalists in their arguments for ratification.

The Tenth Amendment has become a rule of construction[5] directing the courts how to interpret the Constitution. It essentially tells the courts to follow the law of agency, that a principal, in this case the PEOPLE, (and their alternate agent, the States) retain authority over all subject matter not outlined in the agency agreement (the Constitution).

The Purpose of the Tenth Amendment

This amendment was to answer concerns that the Constitution’s central government would not usurp powers intended to remain with the States and the people. The key principle of the Constitution was originally quite simple: positive grant of enumerated powers.

The people appointed the federal government their agent for certain purposes and their own states for other purposes. The Tenth Amendment explains that the federal government is authorized to exercise only those powers which are specifically given to it. It makes clear the principles of federalism underlying the Constitution.

The Tenth Amendment and McCulloch v. Maryland

The Tenth Amendment and McCulloch v. Maryland

In 1819 Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland turned aside the concept that the Tenth Amendment limited the central government to specific constitutionally granted powers. Marshall ruled the Constitution granted not only the enumerated powers, but an extensive collection of implied powers.

Marshall emphasized a word missing from the Tenth Amendment. The Articles of Confederation[6] had limited the central government as follows:

“Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated.” (emphasis added)

Marshall ruled that since the Tenth Amendment differed from Articles of Confederation provision by omitting the term “expressly” the Amendment’s intent was to give Congress an array of implied as well as explicitly delegated powers. Since the central government’s power was not “expressly” limited, its power could expand well beyond the specific constitutional grants of authority.

The Necessary and Proper Clause

To allow government authority to be exercised in areas well beyond limited constitutional grants, Marshall relied upon the Necessary and Proper clause:

“The Congress shall have Power … To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”

In determining the Tenth Amendment contained no express limitation provision and that the Congress had the authority to make “necessary and proper” laws to execute the enumerated powers Marshall’s ruling was contrary to the Federalist ratification arguments.

The Tenth Amendment in the 21st Century

Marshall set the stage for Tenth Amendment atrophy. That is what happened over the centuries. The listing of subjects reserved to the states promised by the Federalists has been subject to intrusive, and in some instances exclusive, federal control. The fears of the Anti-Federalists have come to fruition. The Supreme Court has given the Tenth Amendment some life in recent years with rulings limiting the federal government from commandeering state government to execute federal policy, but those victories for local government are few.

The states cannot rely upon the federal courts to truly act as a limit on federal power.[7] The states can only protect their constitutional prerogative through their own actions. There are state exertions of 10th Amendment powers of late with state actions on the subjects of both marijuana and the Second Amendment right to bear arms. In some states 10th Amendment arguments are put forward in opposition to Common Core. The 10th Amendment’s vitality depends not on court decisions, but on strong state leaders acting in the local interests of their citizens.

For an example of the 10th Amendment at work in a positive fashion, consider the nation’s most respected profession, nursing.

[1]The Federalists

[2]Article II’s section 8, primarily defines the subjects upon which Congress can pass laws. The Federalists argued the legal maxim of designatio unis: The designation of one is the exclusion of the other. The idea being that by naming specific powers, any unnamed authority was withheld from the federal government.

Specific powers of the President and Supreme Court are found in Articles II and III respectively, with the same argument applied.

[3]The Constitution provides two methods to propose amendments. See Article V for a full explanation. There are multiple contemporary efforts to call an Article V convention.

[4]The second amendment proposed was ratified 202 years later, becoming the 27th Amendment.

[5]A “Rule of Construction” is a legal concept developed over time that tells a court how to read a document or a law. The principles behind these rules are generally to arrive at the intent of the people who created the document or passed the law.

[6]This was the “operating agreement” between the States from 1776 to 1789 when the Constitution went into effect.

[7]As a practical matter, federal courts are 1/3 of the federal government. When the 17th Amendment provided direct election of the Senate, rather than appointment by state legislatures, the voice of the states in the Congress was silenced.

[…] of local governments was not delegated to the federal government. Absent that delegation the Tenth Amendment leaves establishing local government to state […]