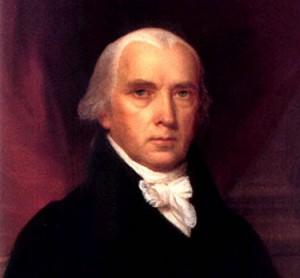

On December 16, 2013 US District Court Judge Richard Leon took on arguments[1] that over the years have been used to expand government intrusion into American life in ways that would have left James Madison “aghast”.[2]

His opinion in Klayman v. Obama finds much of the National Security Agency’s (NSA) surveillance collection of “telephony metadata” [3]process unconstitutional. Judge Leon’s 68 page opinion rejects the conventional arguments the government makes for this program. [4] (On August 28, 2015, an appellate court sent this case back to Judge Leon. See: Appellate Court: Plaintiffs Offered No Proof NSA Violated Their Rights)

In doing so, he references British government conduct that contributed to the American Revolution, privacy as understood by the Founders as a touch point, societal understandings of “privacy”, practical considerations of “standing”, and undefended government assertions of “national security”. The opinion is an American Manifesto.

“General Warrants” and “Writs of Assistance” Made the Arguments for Revolution

Judge Leon’s refers to “general warrants” and “laws that allow searches to be conducted indiscriminately”.[5] “General warrants” sowed the seeds of the American Revolution. The Fourth Amendment’s[6] history can be traced to the British practice of issuing “general warrants”[7] known as “Writs of Assistance”. A “writ of assistance” required subjects loyal to the king to “assist” the king’s agents in the conduct of a search.

The NSA program requires the aid of private companies such as Verizon, AT&T and Sprint in the collection of metadata. It bears an eerie resemblance to the requirements of the 18th Century British writ. The British were uncertain about what they were looking for, and not certain where to look for it, but they could require the help of others in the search. These “general warrants” were a significant factor in the future Boston Massacre, Boston Tea Party and American Revolution.

Reasonable Expectation of Privacy and Societal Expectations

The Fourth Amendment of the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. In the following centuries the Supreme Court carved out exceptions to the Amendment’s requirement that law enforcement obtain a warrant from a judge before conducting a search. The legal concept of “reasonable expectation of privacy” has been involved in many exceptions. The rule is the government does not need a warrant to search or seize something that someone cannot reasonably expect to be private.

Often, courts define “reasonable”[8] differently from what society believes. Many Americans feel when they trust someone with information it is “reasonable” that information will remain private.[9] Historically, this is not the position of the courts. [10]

The 1979 Supreme Court case, Smith v. Maryland set the standard for what courts call “reasonable”. Smith, at its most basic, says that when someone dials[11] a phone number he knows information is transmitted to a third party (phone company) and the phone company keeps call records. With that knowledge there cannot be a “reasonable” expectation the information is private.

Judge Leon points out that the world has changed in the 34 years since Smith.[12] He outlines those changes in detail, and the societal expectation of privacy that has developed around the cell phone-centric culture and online purchase. He relies upon a broad consideration of privacy that states a constitutional violation occurs when “the government violates a subjective expectation of privacy that society recognizes as reasonable…”[13] He opines that if people do not expect privacy in a technological world, it is because their government has tried to train them not to expect privacy.[14]

Technical Legal Point of “Standing” and National Security Argument Shredded

Often federal courts dismiss complaints against the government on the basis of a lack of “standing”. [15] The government in this case asserted that Mr. Klayman could not show an injury and therefore could not sue. Judge Leon’s answer to this: “It has long been established that the loss of constitutional freedoms, ‘for even minimal periods of time unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury.’”[16]

The government asserted the NSA program is vital to national security and has prevented 54 terrorist attacks. Judge Leon responds that although the government could have provided him privately with evidence in his chambers: “no proof of that has been put before me.” [17]

A Courageous Judge and Patriot

Judge Leon’s opinion will certainly not be the last words by a judge on this subject, but it surely should be words that are read by all Americans.[18] The issues involved go to the very heart of being an American and being free. James Otis provided the philosophical basis for the American Revolution opposing the “Writs of Assistance” in a Boston courtroom on February 24, 1761 with a young Future Founding Father, John Adams, in the audience. Otis’ arguments that day became the arguments for Revolution.

Judge Leon pointedly reminds his colleagues of their duty: “… we must assure preservation of that degree of privacy against government that existed when the Fourth Amendment was adopted.”[19]

Listen to Discussion on Constitutionally Speaking

Listen to the discussion with Attorney Max Macoby on Constitutionally Speaking about the NSA and the Fourth Amendment:

https://soundcloud.com/david-shestokas/constitutionally-speaking-4th

[1] Judge Leon acknowledges that his opinion may conflict with at least three other federal trial courts on page 63 of his opinion. Judge William Pauley would take a nearly opposite view of the NSA program less than two weeks later.

[2] On page 68, footnote 67.

[3] The opinion contains a great explanation of the NSA electronic surveillance program and provides an understanding of technical matters like “telephony metadata”.

[4] Many of which have been accepted by other federal courts. Judge Leon opinion, page 63. In considering other judges who may not agree with Judge Leon, it is worth considering that the courts themselves are 1/3 of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. Since the 17th Amendment and the direct election of Senators made all Senators strictly federal officials, there has been no check on appointment of judges who believe in expansion of federal government power.

[5] Judge Leon Opinion, pg. 64.

[6]“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated; and no Warrants shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

[7] The British warrants were in effect for years, much like the NSA program’s ongoing program that, under current law, can continue into the undetermined future.

[8] “Reasonable” in legal terms is usually considered to be an “objective” standard. That is, for a particular case, it does not matter what the individual actually involved in the case believes, but rather what some mythical “reasonable person” should believe. The courts define what this mythical person should believe. The actual belief of the person involved in the case typically is irrelevant to the court. The actual belief of a real person is referred to as “subjective” and in the realm of privacy law, usually receives little consideration.

[9] Certainly many look for those assurances from websites and other online activities. That’s why most sites include a privacy policy tab. The fact that these policies are seldom read is unrelated to the comforting effect that such a tab exists.

[10] Absent a recognized privilege like attorney/client, doctor/patient, priest/penitent once information is transmitted to a third party, the courts generally hold there is no “reasonable” expectation that the information is private.

[11] In 1979 when Smith was decided telephones still had dials.

[12] While this is clearly obvious to most, it is not something often mentioned by judges. This recognition by Judge Leon is how he comes to conclusions different than other federal judges, and still give proper deference to the Supreme Court.

[13] Kyllo v. United States, 533 US 27, 33 (2001)

[14] Judge Leon’s Footnote 60 on page 55, talks of Americans growing up in a post-cell phone, post-Smith, post-PATRIOT ACT age having no idea of American traditions and believing that government monitoring of their lives is normal.

[15] “Standing to sue” is a legal principle defining circumstances which must exist before a party is entitled to have a federal court decide the merits of his case. The requirement of “standing” comes from the Constitution’s Article III grant of power to federal courts in “cases” and “controversies”. To have standing a party must show the court there is an injury, the defendant caused the injury, and the court has power to do something about it.

[16] Mills v. District of Colombia, 571 F.3d 1304, 1312(D.C. Circuit, 2009) (quoting Elrod v. Burns, 427 US 347, 373 (1976))

[17] Judge Leon opinion, page 62, footnote 65.

[18] It’s a 68 page opinion, and though there is much legal argument, much is in plain common sense language. The footnotes are perhaps where great insights are to be found.

[19] Judge Leon opinion page 63. That is not just the duty of judges; it is the duty of all Americans to jealously guard our freedoms.

[…] right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, […]