Beginning with The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut in 1639,[1] Americans grew increasingly accustomed to local self-government. They also learned the freedom and liberty that came along with a benign distant central government accepting local citizens’ control of local law. Over time, Americans came to live in a world perhaps described as “quasi-federalism”.[2]

Beginning with The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut in 1639,[1] Americans grew increasingly accustomed to local self-government. They also learned the freedom and liberty that came along with a benign distant central government accepting local citizens’ control of local law. Over time, Americans came to live in a world perhaps described as “quasi-federalism”.[2]

Among the men who would become known as Founders, political philosophies, particularly John Locke’s Natural Law theories, explained the basis of legitimate government as the protection of each individual’s natural rights and personal sovereignty.

The colonial experience had shown the tenuous aspects of life when a benign central government allowing local governance became a tyrannical central government asserting absolute power. Without institutional protections, freedom and liberty enjoyed while a distant ruler was paying little attention could be snatched away in an instant.

The combination of philosophy and experience would result in American Federalism institutionalized in the Constitution.

Declaration of Independence Details Natural Rights and Purpose of Government

Much of The Declaration of Independence consists of a list of grievances against King George,[3] but the document is much more. Its first paragraph tells the world and the people of the nascent nation that “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” were THE principles that legitimized the United States. The second paragraph summarizes the Natural Law principles that men are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” and the purpose of government is to “secure these rights”.[4]

The Declaration of Independence Creates a Challenge

The challenge that lay ahead was to structure a government that would secure a citizen’s inalienable rights[5] and yet govern effectively. The Articles of Confederation[6] created a central government that was too weak to pose any danger to individual liberty, but also too weak to govern. The Declaration’s challenge remained May 25, 1787 when the Philadelphia Convention[7] opened and chose George Washington as its president.

The challenge that lay ahead was to structure a government that would secure a citizen’s inalienable rights[5] and yet govern effectively. The Articles of Confederation[6] created a central government that was too weak to pose any danger to individual liberty, but also too weak to govern. The Declaration’s challenge remained May 25, 1787 when the Philadelphia Convention[7] opened and chose George Washington as its president.

The proposed answers to the challenge would be found in Separation of Powers among the federal branches and the divided sovereignty between the central government and the states that became American Federalism.

Separation of Powers to Limit Government and Preserve Liberty

The Founders had seen that tyranny developed when the functions of government coalesced into a single entity. Theories of separating government functions to preserve freedom had evolved over 18 centuries of human thought from the Greek philosopher/historian Polybius in the 1st Century BC to Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (Montesquieu), who heavily relied upon Polybius in his 1748 treatise Spirit of the Laws.

The Founders had seen that tyranny developed when the functions of government coalesced into a single entity. Theories of separating government functions to preserve freedom had evolved over 18 centuries of human thought from the Greek philosopher/historian Polybius in the 1st Century BC to Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (Montesquieu), who heavily relied upon Polybius in his 1748 treatise Spirit of the Laws.

James Madison opens Federalist No. 47, The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts, by pointing out the need to explain how “the preservation of liberty requires that the three great departments of power should be separate and distinct.” Madison’s relies on Montesquieu for the principle that: “There can be no liberty where the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or body of magistrates,” or, “if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers…”

The Constitution’s Articles I, II and III established the legislative, executive and judicial departments.[8] The method of selection varied for each as did the terms of office. This set of institutional protections for liberty was defined. This did not complete the institutionalized protections for liberty and meet the challenges arising from The Declaration.

Separation of Powers an Insufficient Safeguard for Liberty’s Preservation

While the Constitution’s drafters separated and balanced powers between the central government branches, colonial experience demonstrated to them such institutions did not create a guarantee. They needed to look no further than England.

Though the English Bill of Rights of 1689 had greatly reduced the authority of the monarchy and marked the beginnings of Parliamentary Sovereignty, the king retained significant power. Among the royal powers retained well into the 18th century and to the time of the American Revolution: control of the bureaucracy and military, appointment of judges and ambassadors, the right to assent or not to legislation.[9]

George III assumed the English throne in 1760. From George’s coronation to 1770, England had six Prime Ministers.[10] In 1770, George’s political ally, Lord Frederick North became Prime Minister. The British Parliament had been adrift for 10 years and then with the George III/Lord North alliance, executive and legislative power coalesced together. From George’s 1763 proclamation[11] to The Intolerable Acts of 1774, Britain sought ever increasing control over the colonies.

As a practical matter, the executive and legislative powers had been merged by political forces. When the Declaration listed colonial grievances, it was against George. The document never mentions Parliament, as all powers had merged into the person of George.

The Founding Fathers learned that separating power technically among units of government did not prevent political circumstances from unifying that power.

American Federalism: Additional Protection for Natural Rights and Liberty

Drawing upon 1800 years of political thinking of how best to have government and yet maintain the personal sovereignty possessed by each individual under Natural Law, the Constitution’s drafters separated the central government’s functions among three branches: legislative, executive and judicial. The colonial experience had taught that this was not enough.

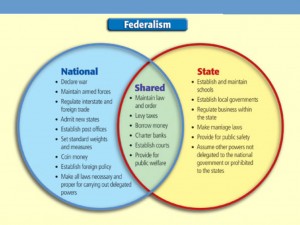

To further protect against the tyranny that results from a concentration of power, the Constitution would divide the elements of sovereignty between the central government and the states.[12] The original Constitution’s division of sovereignty was institutionalized with the following provisions:

Article I, section 2 prohibited direct federal taxes unless apportioned[13] among the States.

Article I, section 3 provided that State legislatures choose Senators, giving the states themselves representation in the federal legislature.

Article I, section 8 specifically enumerates the subject matter upon which Congress may legislate.

Article IV recognized state sovereignty in the relationships between states with the command that “Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State.”

Article V made the states and the federal government full partners in making amendments to the Constitution.

Article VI directs that state and local officials must take an oath to support the Constitution, and defines a hierarchy of law

Alexander Hamilton sums up the effect of the provisions in FederalistNo. 9:

“The proposed Constitution, so far from implying an abolition of the State governments, makes them constituent parts of the national sovereignty, by allowing them a direct representation in the Senate, and leaves in their possession certain exclusive and very important portions of sovereign power…”

James Madison, in FederalistNo. 45, denotes power reserved to the States as the ultimate protection of liberty:

James Madison, in FederalistNo. 45, denotes power reserved to the States as the ultimate protection of liberty:

“The powers reserved to the several States will extend to all the objects which…concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people…”

The Ratification Debates: Implicit State Sovereignty Not Enough

Pursuant to Article VII, the Constitution would become effective upon ratification by nine States. For many delegates to the state conventions, the Constitution’s structure, Hamilton’s assurances and Madison’s arguments were not enough. Explicit statements as to a person’s rights and state power were desired. Proponents of the Constitution promised to do so once it was in operation. In 1791, in keeping with that promise, the Bill of Rights was ratified. The Tenth Amendment stated clearly what the Constitution had done structurally:

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

American Federalism: Experience, Philosophy and Ratification

The colonial experience, from The Fundamental Orders to the excesses of King George and the Natural Law philosophy as expressed in the Declaration of Independence came together to produce a concept unknown before: American Federalism.

It was put into operation in a way no nation had done before: specific ratification by the people of the territory in which the government was to operate.

American Federalism, the division of sovereignty by subject matter between governments in the same territory, was born in recognition[14] of the belief that each individual owns Natural Rights and the purpose of government is to protect those rights.

“State’s Rights” May be a Misnomer

When considered in light of its development, discussions of American Federalism that emphasize the importance of “state’s rights” may be off the mark. Federalism’s ultimate purpose is to protect the Natural Rights of each individual American. A state’s right then, indeed its obligation, is to defend each citizen’s Natural Rights.[15]

__________________________________________________________________

[1] See, American Federalism: Source, Purpose and Establishment Part I. A historical examination of the ideology of American Federalism by Professor Alison LaCroix is a recent scholarly work on the subject.

[2] While political scientists have applied “quasi-federal” to certain eras in Canadian history and to the government of India, an unsigned answer at Wiki.answers.com defines the term in a way that expresses the relationship as it developed between Britain and her North American colonies: “A division of powers between central and regional government that has some features of federalism without possessing a formal federal structure.”

[3] The disdain for King George is exemplified by an unverified, but certainly plausible, quote from John Hancock upon completion of his famous signature: “There, I guess King George will be able to read that!”

[4] The impact of John Locke’s theories of Natural Law on the Founders cannot be overstated. Compare Jefferson’s: “all men are created equal” to Locke’s “all men by nature are equal”.

[5] A government must be able to “secure” rights, but not be so strong as to itself be a danger to those rights.

[6] The Articles of Confederation was the United States’ “First Constitution”. It was an agreement among the states adopted by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, but not effective until March 1, 1781 when Maryland became the necessary 13th state to ratify. On March 4, 1789, the Constitution went into effect, superseding the Articles.

[7] The delegates to the 1787 Philadelphia Convention had been charged with proposing amendments to the Articles. Instead, on September 17, they emerged with the proposed Constitution.

[8] No. 47 is primarily devoted to addressing objections to the Constitution that the lines between the branches are not distinct, and that the functions are “mixed” rather than completely separate. Examples of overlap include the president’s power to appoint judges and the Senate’s power to approve, or the authority of the two political branches to define, in many instances, the jurisdiction of the judiciary. Madison defended such mixtures with examples of the same from state constitutions and clarifications of Montesquieu.

[9] Technically the British monarch’s prerogative to veto Parliamentary legislation continues to this day, but it has not been used since 1707. The system became more “presidential” than “royal”. Montesquieu had seen the division between king and Parliament as a separation of power.

[10] The Prime Minister (head of the majority party of the House of Commons) is now head of government in England, while the monarch is the head of state.

[12] Beginning with the premise that “sovereignty” belongs to each individual, it becomes like any other property. Parts of it can be granted to others. An owner of land can grant oil rights to one party, water rights to another, and possession rights to a third, subject to the other grants. The owner of any property has the authority to appoint an agent to manage that property.

[13] Determined by population, like the make-up of the House of Representatives.

[14] Certainly other, practical political elements were at work in forging a consensus to adopt the Constitution, such as the established orders within each state. However, the Natural Law protections and divided sovereignty combined nicely to address those considerations as well. That may be a discussion for another time.

[15] The institutions established originally have been upset through the Civil War, and the 14th, 16th and 17th Amendments. The Founder’s distrust of a strong central government and the systems put into place to prevent an accumulation of power have been profoundly displaced.

[…] The Constitution’s division of “subject matter jurisdiction” between government units to protect individual Natural Rights is discussed in Part II. […]